Your name is Betsy Braddock and your body will never be yours. You’re British and a mutant. You’ve got purple hair (most of the time). You’re a psychic (most of the time). You’ve got this pink butterfly power signature to differentiate you from the million other mutant psychics wandering around in X-Men comics. And your body is a question. Your body is in question, is presented for interrogation — often at the center of a page, posed just so.

Here, usually, would be the place where we discussed the gaze of the artist and the viewer, the reader. Its effect on women’s bodies. The prurience of comic books, always heating the surface of the page, stored in the marrow of comic book storytelling’s origins in pulp fiction in the early twentieth century. But I don’t know about most of those things, Betsy. I’m a random Catholic theologian who likes comic books, and I’m impoverished of many modern ideas. I bet I’ll get details about you wrong. But I don’t care. Let us speak, together, of the sacraments.

Augustine calls the sacraments “sacred signs.” Sacraments are “visible signs of invisible grace.” Sacraments are interesting because they are simultaneously symbolic and real, sacramentum et res. They are what they signify: the waters really do cleanse the body and the soul. Still they signify: we do not see, with our eyes, the grace “really” operating through the symbol of water. It easy to lose the one thing or the other, the reality or the signification, but sacraments are both. Or again, it is easy to lose the sensuality before the invisible “idea,” but the power of the sacraments is in how they’re undivided. Sacraments require sight with two eyes: physical, spiritual.

Comic books tell stories by being sensual: visible, vivid. There is narrative and dialogue, but also the page itself: inked in bright colors. Betsy, you’re a “classic” comic book character. Your world is primarily brightness and broadness. Your life is measured in months. You’re iterated. To cohere, you’ve got to scrape by on visual cues, symbolic heft, narrative tropes, and superpowered cataclysms. You’re not quite a psychology, so you’ve got to signify. You’ve got to take shape in the space between visuality and dialogue. And, over the decades, that shape of yours will trouble you and the narratives you’re in.

At first, you’re just Brian Braddock’s psychic twin sister. You fly a plane. (Later, you’ll add supermodel and spy to your resume.) You’re a member of a family of British aristocrats. It’s the 1970s and Marvel has a UK imprint. Captain Britain, Brian, your brother, is a new hero. He’s an attempt to appeal to a British audience. This… does not work. But Captain Britain and his two comic series Captain Britain and Excalibur will have a habit of showing up intermittently. The stories in Excalibur will be populated by Arthurian figures and by mutants, making the world and the hero essentially a branch of the X-Men.

Betsy, you’ve got purple hair and you’re a psychic, which is cool. Writer Chris Claremont, who will bring about and shape the success of a transformed X-Men franchise in the 1970s and 1980s, likes you. So your psychic power becomes a mutation and you join the X-Men at the mansion as one of them. It’s the 1980s and Jean Grey is dead for now.

But first, Betsy, you lose your eyes. First, you lose your mind. This is your baptism as an X-Man: your wrecked face and broken will.

For a brief, shining moment, you’re Captain Britain, taking up the mantle when your brother has put it down. Bravely, you set out in the guise of one of Marvel’s weirder heroes — the one with the patriotic multiversal responsibilities and King Arthur enemies and such. You last basically one issue. And then a villain tears your eyes from your head.

Your brother finds you. Here, perhaps, is the first real cleaving-apart of Betsy Braddock. It’s not in your physical loss, but in its visual presentation: Brian’s sorrow is gorgeous and yours is hidden. It wouldn’t do, probably, to actually show the blood running down your cheeks beneath your empty eyes. It’s the 1980s. That would be 1990s gore levels. But still. The sacramentum is his face and the res is you. You’re split across the page, Betsy. Your pain is expressed on someone else’s face. It makes the moment sad but also unsettling. Looking backward, it foreshadows the unsettling strangeness of your later fate. You’re there and not-there, Betsy, near and far. As you will be so many times in your future.

Your baptism is not over. A short time after this, the most chaotic villain in the X-Men universe — Mojo — steals you away. He and his tortured slave, Spiral, force new eyes into your head. Bionic eyes that can transmit the drama of the X-Men universe to the multimedia extravaganza that is the “Mojoverse.” You become Mojo’s slave. The X-Men rescue you. Now you arrive at that looming mansion, where a person becomes a hero. But if heroism is a kind of mastery in comic book stories, you’re already a contradictory hero, having been defined so far by your courage and beauty and the things done to you.

Comic book characters live unimaginable total lives. They’re stretched across decades as they’re written, and they’re compressed down to hours and days as they never really, finally age. They’re narrative creatures who are both distended and intensified. Their core resilience is necessary to them, to their narrative being, whose being is fundamentally to persist, to be in another story, to be brave again. Minor or unpopular characters die. But Jean Grey dies and lives again.

In their modern forms, loosely beginning in the 1980s, comic book characters have memories, and, equipped with memories for a “before” and an “after,” they can and do endure change. They start to resemble literary characters more closely because they’re dynamic in ways they weren’t before. They have personalities and motivations and relationships particular to each of them. But still, they’re never quite continuous continuities or narrative wholes. Their world is still the world of iterative pastiche. Comic book characters are Gestalten. They’re vivid so they can be recognized, literally, at a glance. And so we can endure their contradictions.

Catholics are, or at least can be, naive about the relationship between “visible” and “invisible” in human bodies, the physical page of our self-expression. The sacramental analogy by which Catholics understand our own bodies is sometimes over-determined, so that the immobility of sacramental symbols (in order to render them continuous, to cleave them to a moment in the life of Christ) is applied to human bodies. In uncareful hands, the model for human bodily becoming is rendered too inflexible to be real: “be what you are, which in a sense we already know, and which you ought to know, because we can see it.” You are right here. You are self-evident and clear. You are out-there-now.

But our job is not merely to be but to communicate, to express a hidden “depth.” “As body,” Hans Urs von Balthasar says, “man is a being whose condition it is always to be communicated” (emphasis mine). Necessary to our own being bodily ourselves, he says, is what he calls “expressive play.” To be a human body is to be creatively self-expressive. In a sense, uniquely self-expressive, since the only “self” you know from the inside is you.

What do you express, Betsy Braddock? There on the page? Your physicality is not like Mystique’s, the forbidding and cunning and ageless villain and antihero, who haunts any face she chooses. In the movies, Mystique is a henchman, a kid sister. Alluring. Maybe confused. In the comics, though, Mystique is her own boss. Meaner. Even when she’s on a team, Mystique is her own boss, which is a fundamental element of her difficulty for our heroes: she cannot really be controlled. That is, in a sense, her purpose. Mystique is pure willing made flesh, a shapeshifter who can with a thought totally unmake and remake herself, transforming into anyone at all. Perfectly. Seamlessly.

Your body, Betsy Braddock, is not so free. Your will is more constrained. It’s not that you lack power. You can and do, when pressed, take over someone else’s mind. You can make them see what isn’t there. You can be a kind of psychic group chat for the X-Men. You were a British spy-commando or something — and a supermodel — so you can fight, too. Gorgeously. With your impossible powers in a fantastic universe, you develop precise and considerable control. You’re a hero. But despite everything about you, it is not your power but your helplessness that will be the pathos of the decades that follow. That and swords.

What happens next is complicated, but here is its simplest version: Spiral and Mojo show up again and your mind is forced into another woman’s body. She is a Japanese assassin. Her mind, unmoored, is forced into yours. Your two psyches splinter and integrate and then sever from one another. Or something like that. Half a dozen retcons make your strange story stranger, Betsy Braddock. Time folds like pages, frayed edges touching and separating, as writers lift the memory of your fate and try to write it again.

You both die, after a fashion. This woman and you. Your body dies and she, this stranger, dies with it. It’s like dying your death without you. While you live on. While she’s your face and your voice and she’s dead. You’re alive and you’re not yourself. You’re dead and you’re still here.

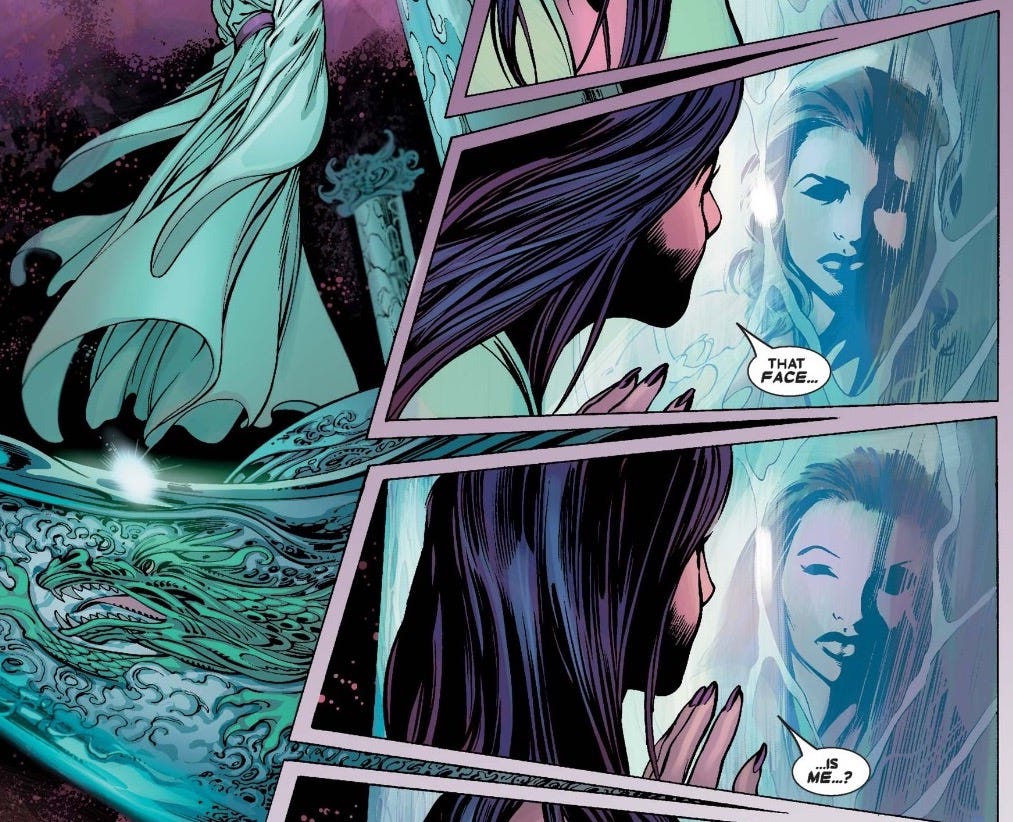

You’re so so cool and so popular, Betsy Braddock. As this alienated self. You’re never more popular among fans. You sell so many comic books. As the “you” that for decades you cannot manage not to be and as the “you” that you are not: they’re you, Betsy. Look in the mirror, at this face and these hands: yours and yours and not yours at all.

All the edges of your rage and violence — you get very angry and violent, and who wouldn’t? — will be doubled by the basic contradiction of being yourself. Structured by tropes about Asian women and ninjas, your body, its sexuality and its brutality, will shape your narrative discord for decades. You’re a female comic book character: you were always sexualized, before and after. But, looking backward, it’s disturbing how sexually available you become when you become an Asian body. It’s not you because you’re not real. It’s the 1990s. It’s the tropes and the symbols by which you are a body, an Asian body (that is not yours), driving the engine of the story. You’re not quite a psychology, remember? You’ve got to scrape by on thematic and visual vividness. Which, in your case, works to sell comic books and to make you narratively impossible but very cool. One time, Betsy, you’ll die and resurrect as Japanese again. Even dead, you couldn’t escape yourself and the strange way you’re not yourself at all.

I said that the sacraments are sacred signs. That they are what they symbolize. There is an honesty there that’s of a piece with a more general Catholic trust that what God has made says something about God. Creation is trustworthy in that sense. It requires complexities like analogizing away from simply identifying God with the world, but still, that world is good, and that goodness indicates something about God, even if we do not actually know what infinite goodness is or what the divine nature is in itself. Even more intimately, the sacraments are what they symbolize. They do what they say. They are trustworthy.

Betsy Braddock, you are, for a very long time, an internal contradiction. You interpose on the page with — well, a sort of lie. You’re not Japanese or a ninja. You’re a psychic, telekinetic mutant with a butterfly visual signature. A commando and a supermodel. Or whatever. Your powers were always on the move, and are on the move still. So at least this is true: for a long while, you were and were not yourself at the same time.

It’s just a story. It’s a narrative mistake — it’s a bad narrative choice — that everyone coped with for decades. But the interruption of the character with this physical confusion is one of the interesting things about her. You, Betsy Braddock, are the supermodel-warrior in a body that she did not model, agonized and angry, running around and stabbing people — like Magneto that one time. He’s Magneto so he’s fine. You got to beat up Spiral, your evil surgeon, too. She’s Spiral so she’s fine.

Your narrative body intervenes with strange questions, Betsy Braddock. It was violence and freedom that mediated your entrance onto a larger dramatic stage with the X-Men. It was violence and freedom — and a very cool sword — that mediated your entrance onto a larger stage still (of popularity). Violence and freedom shouldered you, both at once, lifted you up for viewing. It’s the freedom in you, the narrative self-presence, the sketching of a personality with its visual signifiers, that made the violence serious and human and not merely physical. That made you angry in a way that felt real. Only a free will, after all, can suffer unwillingness: that suffering became narratively yours. So for three decades, you suffered being a body more and more. The racial undercurrents only pulled you into the depths and drowned you in further contradictions.

In 2018, Kwannon, the Japanese woman whose body is yours, gets to be and have her own body. I’m not telling the whole story. Comic books are weird. The point is that Kwannon is now a cool psychic ninja on her own terms (terms that were, and in a sense still are, fundamentally, yours).

You, Betsy, get your own body. Well, not your body. That original body vanished in an explosion of pink light. Or whatever. (Comic books are weird.) So what happens to you is not like returning home after a long journey. It’s like entering a stranger’s house that looks like yours. Nothing you get really gets to be whole. That was never you, Betsy, and in a weird way I’m very grateful to know the broken sacrament of you and I’m very sorry.

How bizarre, the mercy finally shown you, Betsy Braddock. When you become two people in half a dozen retcons, and then finally, really, at last. What else was there to do? The original sin of becoming another body, or of forcing a woman into an another woman’s skin, the racial undertow of the violating act, was too monstrous. And erasing you or Kwannon would have been too monstrous, too. So here you both are, and now you’ll both live on. It is and was always your task to live on, Betsy. Right now, at least, you’re Captain Britain and you still have both your eyes and you saved the world and Otherworld (which I’m still not explaining). It doesn’t matter if people hate it. The point is that it wasn’t what it was before, which you couldn’t be anymore, and the point is that the only way to redeem you was to say something more.

I find redemption by addition an interesting thing. Grace is, in some respects, additive. Not to the divine plan — there’s just the one — put to the human nature it infuses. But I’m a theologian, and can’t be trusted except to find theology in too many places.

Comic book characters are never straight lines. They exist by enduring everything. They transmogrify constantly in the hands of new artists and writers. And if the crisis and confusion of Betsy Braddock’s body has larger meanings, one such meaning is that human beings find their own bodies at once interesting and perplexing. Those bodies signify, but they do not not signify easily. For none of us knows ourselves except very dimly, and the solidness we see when we look at one another conceals our uncertainty and changeability. Not to change, for us — to learn no lessons, to feel no shame, never to rise up transformed — is the worst thing of all.

How strange, your dislocation, Betsy Braddock. In your fantastic and impossible world. How permanent your ruin, as a character who remembers, and who therefore cannot forget wearing a face that wasn’t yours. It’s not the trauma that’s interesting. It’s having to be someone anyway, even a comic book someone, which you are. May you persist. And suggest to us some small thing about the mystery of our own living.